On a sunset cruise during the lockdown, we spotted a well-known boat from The Abacos. FREESPOOL! Why was she six docks down from ours in the Ogeechee River, a far cry from the Sea of Abaco? I’ll confess, it was curiosity, not concern or compassion at first, that had me questioning. It was intriguing, a diversion. Then, reality set in. The winds of Hurricane Dorian had blown her in. She had not fared well through the storm.

I flagged down the boat captain one afternoon as she passed by our dock. The only information I garnered was that she had been bought from a broker and that I was not the first to recognize her. Many other stories surfaced, and Tad Dillon, the new owner, said he began to think he was the only one in the neighborhood who had not fished that boat.

Captain Robbie Robinson, owner of the small retreat on Lubber’s Quarters Cay in The Abacos named Pura Vida, with three cottages and a tiki bar, a 45-foot catamaran, the AlphaCat, and the 36-foot Jersey Devil charter fishing boat, FREESPOOL, generously donated a stay on the four-state-room catamaran each year to our local Coastal Conservation Association which they auctioned off at their annual fundraising event. From the first time he donated, word spread, and Richmond Hill began flocking to The Abacos.

Stories and memories abound of adventures island hopping to Marsh Harbour, Elbow Cay, Man ‘O War Cay, Great Guana and Lynyard Cay; exploring deserted beaches and hurricane-ravaged houses; diving for lobster and starfish; crackin’ conch (and drawing straws for who eats the pistol); fishing, snorkeling, or jumping in blue holes; the infamous parties at Nippers; taking the dinghy to favorite legendary restaurants and watering holes like Pete’s Pub, Cracker P’s, Firefly, and Sea Spray; the candy cane striped lighthouse at Hopetown; visiting Albury boat builders and sail makers; getting fresh bread from Vernon’s and conch salad from Milo; kayaking, paddle boarding or simply floating in the gin-clear water; and daily sunrise, sunset and stargazing parties on the trampoline on the bow. Tahiti Beach comes up time and again, in stories of seeing starfish on the bottom of the sea that looked “as big as a Volkswagen,” and of digging in the sand just off the beach and pulling up sea cucumbers, sea biscuits, and sea glass with every handful.

Todd and Melanie Boyer and Mark and Rhonda Gordon remember their trip to The Abacos. It was two bad days fishing on FREESPOOL in sporty seas. Only two fish were caught the first day (although one, caught by Melanie, was a 60-pound mahi). There wasn’t a single knock down the second day. It was one of the coldest days anyone could remember in the Abacos, and they had to go farther out than the captain had ever had to go to look for fish (so far that the depth finder quit working). And yet, they all said it was one of the most memorable trips ever. It’s not the catch, the weather or the seas that determines a good day and lasting memories. It’s where the boat takes you, not geographically, but in your heart and soul.

So, what made these trips so special, so surreal, and yet so real? The colors, marine life, natural landscape, and flavors were so much more intense and diverse than we were accustomed. And the things we were used to and took for granted were much more in focus. There was no glitz and glamor, just real island life. But there seemed to have been some secret ingredient, that you just couldn’t quite put your finger on, that bound all the others together – like salt. My guess is it was Captain Robbie.

Many people dream of leaving everything and living that life – very few do it. Robbie was one of the few. “I think I was jealous of Robbie,” Rhonda Gordon says. “No, it was more like in awe.” Maybe the first thing one noticed about him was that he didn’t wear shoes. He shed them when he shed his past life. The next thing was his tattoos. Some remember that he had his social security number tattooed on his left side. Others remember it was his blood type. Maybe it was both. He was a former Marine Corps Force Recon Officer. He didn’t talk about himself much or brag, but as Rhonda recalls, you knew “he was no ordinary fisherman and there was some significance to the tattoos and life he had lived.” He was capable, in charge, skilled, and seemed to have an insider knowledge of a vast array of areas. A walk through his cottage and retreat was a peek into his past and the present reality of actually living in the islands, with its limited availability of goods and services. There were pictures of his old life including special missions in Columbia, a hand-made sea glass mosaic shower, a huge pet hermit crab climbing the screen door, and beautiful reclaimed wood. A Beaver Creek cooler some guests had discarded, and he had salvaged and recycled was by the door. He did much of the building, repairs, maintenance, cooking and cleaning himself, and he sourced much of the materials from whatever was found or caught naturally or was left by guests – like some leftover peppers Robert Anderson smuggled in from his own Richmond Hill garden just to make ceviche out of the fresh catch.

Although the closest grocery store was on a nearby island and supplies spotty at best, Robbie could be counted on to almost always pull up something from the sea. He took Robert, Eric Johnson, Fraser Bowen, and John Seckinger spearfishing. “We were snorkeling in about 30-feet of water,” Eric recounts. “It was rough and John got back in the boat. I was watching and yelling to him what was going on. There was a cave at the bottom Robbie said he was going to go down and see if anybody was home. He went down several times. I couldn’t believe how long he could hold his breath. He was a smoker, too. Then, he went down and pulled out a nice, big grouper. I mean, he went inside the man’s house and pulled him out!”

Dorian visited The Abacos September 1, 2019 – Hurricane Dorian, that is – the strongest storm on record to hit there. The catastrophic hurricane is considered the worst natural disaster in Bahamas’ history. Winds of 180 to 220 mph and storm surge devastated The Abacos, leaving an estimated $3.4 billion of damages in its wake. Everyone knew Captain Robbie probably wouldn’t evacuate. Not only would he want to stay with all he had built, figuratively and literally, he was on the rescue team for the islands – one of a few with medic training, a satellite phone, and transportation to the chain of islands. “People were trying to find out how things were, we knew Robbie would ride it out, but crickets,” Rhonda says. “We couldn’t find out anything.” Finally, two weeks later, we found out he had made it, but the life he had built was blown away. “This has been a very challenging ordeal to go through, physically, emotionally, and financially,” he wrote. “I have ridden out seven hurricanes in my little cottage. I have always been prepared and have always cleaned up and put pieces back together. This storm was the strongest on record, and it proved it.”

Robbie lost his home, his livelihood, and way of life. He’s now fishing for trout in the mountain lakes and streams of North Carolina. “It’s a big difference, but a much needed one. The only thing constant is change, and after a couple of rough years, change was made,” he says.

In the eye of the pandemic, that had further crippled The Abacos and stalled its recovery, Tad Dillom discovered FREESPOOL in a boat graveyard in Miami, resurrected her, and brought her to the black water of the Ogeechee. He was having trouble booking charters for his clients and decided to get his own boat. He had boats before, but never an express. He felt like he had missed out on the conversation and action while driving from above and that many fish had been lost by people hanging out in the air-conditioned salon rather than watching their lines.

Tad embraced the boat restoration project during the Covid-19 shutdown. It was a distraction, a challenge, a way of staying mentally busy, and a way to reconnect with his heritage. He had learned boat rebuilding from the ground up from his father who chartered boats. Tad still has all his old numbers. He remembers watching his father do fiberglass work without respiratory protective wear in an old boatyard in Thunderbolt. “It’s a dying art. Most kids won’t see what we saw and learn what we learned,” he says.

The trip up the coast from Miami consisted of stolen electronics, a blown engine, seeing a rocket launch off Cape Canaveral, and a naïve mooring at a spot called Mosquito Bay. He has since repowered with Caterpillar C7 engines, bringing the cruising speed to 30 knots. Plans and timing are all mapped out for the complete project, including renaming the boat SAILS CALL. Tad is in sales, and if he says he is on a “sails call,” he can cover his butt when he’s on the boat instead of working.

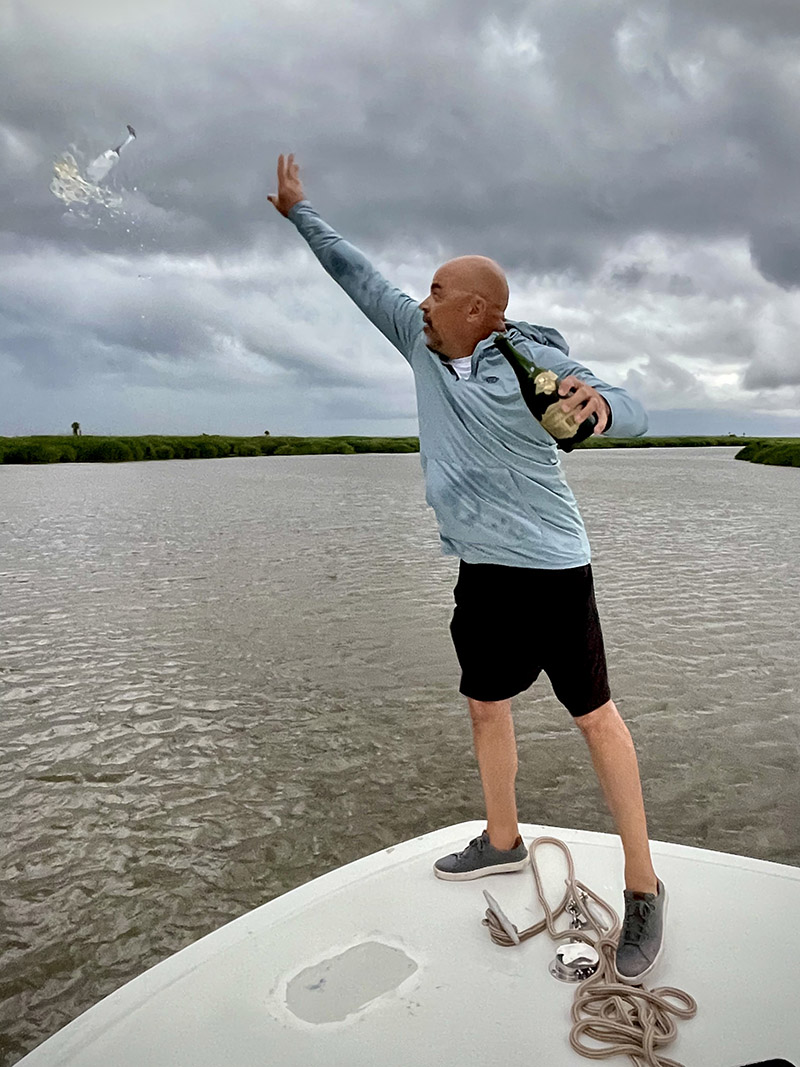

Superstitions abound around renaming a boat. If not done correctly, it can bring on bad luck or worse, the wrath of the gods of the sea. Legend holds that every vessel is registered on the Ledger of the Deep which is presided over by Poseidon (or Neptune). A ceremony must first be performed to purge every trace of the boat’s previous identity and its name on the ledger. No items displaying the boat’s new name can be placed on the boat until after the ceremony. It opens by invoking and flattering the mythical god, then a metal tag with the old boat name written in water soluble ink is thrown overboard, and a drink offering of Champagne is poured into the sea from East to West. Next, the mythical gods of the four winds must also be invoked and equally flattered and offered Champagne. Lastly, the new name is revealed, and all get to celebrate and toast with the remaining bubbly.

No ceremony can truly purge the past, nor would we want it to, but hopefully it will ensure a fair weather forecast for Sails Call. “I think it gives it a good vibe,” Tad says about the nostalgia surrounding the boat. Buoyed by the priceless lessons learned at the feet of his father, he is eager to revive, renew and enhance the vessel with his own hands.

Cheers to a new name, new friends, new winds, and “here’s to living out life in the boat we are in.”